Season of birth effects on elite junior tennis players’ world rankings

Abstract season of birth effects on elite junior tennis players’

Skewed month of birth distributions have been discovered in many sports including Ice hockey (Barnsley et al., 1985; Boucher et al., 1994), soccer (Brewer et al., 1995) and basketball (Thompson et al., 1991). A skewed month of birth distribution will typically have more players who were born in one quarter of the year than any other and there will be a decreasing number of players who were born in the successive quarters. There is a skewed month of birth distribution of tennis players participating in the singles events of Grand Slam tournaments with more players than expected being born in the first half of the calendar year (Edgar and O’Donoghue, 2005). It is thought that the cut off date of January 1st for ITF (International Tennis Federation) is responsible for this skewed month of birth distribution. Indeed, there is considerable evidence that the skewed month of birth distributions observed in soccer participants result from the cut-off date for the junior competition year (Brewer et al., 1995; Musch and Hay,1999). Simmons and Paul (2001) noted that the England schoolboy soccer international squad and players from the English Football Association youth squad had different skewed month of birth distributions that were associated with the two different cut-off dates that applied. Musch and Hay (1999) found that month of birth distributions for top league soccer players reflected the cut-off date for junior competition in Australia, Brazil, Germany and Japan unaffected by the different hemispheres, climates and cultures of those countries. Furthermore, when the start data of the junior competition year in Australia changed, it eventually produced a corresponding shift in the distribution of month of birth of participants. Previous research into season of birth effects on tennis participation has been based on cross-sectional studies (Dudink, 1994; Baxter-Jones, 1995; Edgar and O’Donoghue, 2005) rather than tracing the participation of players over time. Therefore, a longitudinal programme of research has commenced to track the participation of players over the course of their careers. This will allow changes in participation levels and success of players born in different parts of the year to be compared. Specifically two groups will be compared; those born in H1 (from 1st January to 30th June inclusive) and those born in H2 (from 1st July to 31st December inclusive). The scope of the research will be restricted to players born in 1987 or 1988. The purpose of the current paper is to report on the first three years of the longitudinal study.

Introduction

Skewed month of birth distributions have been discovered in many sports including Ice hockey (Barnsley et al., 1985; Boucher et al., 1994), soccer (Brewer et al., 1995) and basketball (Thompson et al., 1991). A skewed month of birth distribution will typically have more players who were born in one quarter of the year than any other and there will be a decreasing number of players who were born in the successive quarters. There is a skewed month of birth distribution of tennis players participating in the singles events of Grand Slam tournaments with more players than expected being born in the first half of the calendar year (Edgar and O’Donoghue, 2005). It is thought that the cut off date of January 1st for ITF (International Tennis Federation) is responsible for this skewed month of birth distribution. Indeed, there is considerable evidence that the skewed month of birth distributions observed in soccer participants result from the cut-off date for the junior competition year (Brewer et al., 1995; Musch and Hay,1999). Simmons and Paul (2001) noted that the England schoolboy soccer international squad and players from the English Football Association youth squad had different skewed month of birth distributions that were associated with the two different cut-off dates that applied. Musch and Hay (1999) found that month of birth distributions for top league soccer players reflected the cut-off date for junior competition in Australia, Brazil, Germany and Japan unaffected by the different hemispheres, climates and cultures of those countries. Furthermore, when the start data of the junior competition year in Australia changed, it eventually produced a corresponding shift in the distribution of month of birth of participants. Previous research into season of birth effects on tennis participation has been based on cross-sectional studies (Dudink, 1994; Baxter-Jones, 1995; Edgar and O’Donoghue, 2005) rather than tracing the participation of players over time. Therefore, a longitudinal programme of research has commenced to track the participation of players over the course of their careers. This will allow changes in participation levels and success of players born in different parts of the year to be compared. Specifically two groups will be compared; those born in H1 (from 1st January to 30th June inclusive) and those born in H2 (from 1st July to 31st December inclusive). The scope of the research will be restricted to players born in 1987 or 1988. The purpose of the current paper is to report on the first three years of the longitudinal study.

Methods

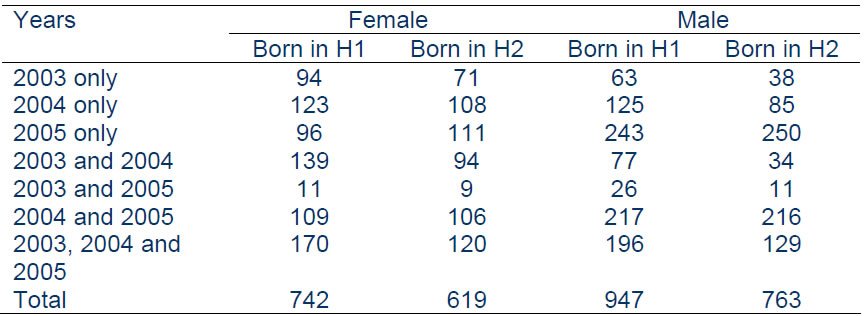

The junior world rankings of 1987 and 1988 born players competing in the ITF junior circuit were traced over a 3 year period from 2003 to 2005 inclusive. The name, nationality, date of birth and world ranking of all 3071 tennis players born in 1987 or 1988 who achieved any junior ranking points in 2003, 2004 or 2005 were obtained from the end of year ITF junior rankings (www.itfjunior.com accessed 31/12/03, 31/12/04 and 31/12/05). It was necessary to sort the details of the players with ranking points in each of the three years into gender then nationality then birth date then name order so as to match each player’s record from different years within a single data sheet of 3071 players. There were some female player who had changed their names due to marriage and one player from Chinese Taipei whose name was recorded in 3 different ways (once with the two parts of the name joined, once with the two parts of the name separated by a space and once with the two parts separated by a hyphen). There were some other players who had changed their nationality over the three year period. Table 1 summarises the number of male and female players born in each half of the year who had achieved ITF junior tour ranking points in the different years for which data was recorded. A minority of 615 of the 3071 players were ranked in all three years from 2003 to 2005.

Table 1. Number of 1987 and 1988 born tennis players achieving ITF junior ranking points in different years.

Chi square goodness of fit tests were used to compare the proportion of different sub-groups of players with theoretically expected proportions assuming equal number of births on each day of the calendar year. Therefore, a fraction of 181¼ / 365¼ of a group would be expected to be born in H1 and 184 / 365¼ of the group would be expected to be born in H2. Chi square tests of independence were used to compare the proportion of players born in each half of the year who entered or exited the rankings in particular years and to compare the proportion of players born in each half of the year who rose in the rankings over a 1 or 2 year period. The change in median world ranking of players was compared IV Congreso Mundial de Ciencia y Deportes de Raqueta between players born in each half of the year using Mann Whitney U tests. For each of the inferential procedures used in the study, a P value of less than 0.05 indicated a significant difference or association.

Results

Table 2 shows that in each year from 2003 to 2005, there were significantly more male junior players achieving ranking points who had been born in H1 than H2. There were significantly more female junior players achieving ranking points who had been born in H1 than in H2 in 2003 and 2004 but not in 2005. In the case of both the male and female players, the chi square value and hence the level of significance decreased steadily from 2003 and 2005. The total number of 1987 and 1988 born male players who were ranked increased from 2003 to 2005 as older players gradually moved into senior tennis. However, the total number of 1987 and 1988 born female players who were ranked in the ITF junior rankings decreased from 2004 to 2005, possibly due to some of these players participating in senior competition before the age of 18.

Table 2. Half year of birth of 1987 and 1988 born players with junior ranking points in each year.

Table 3 summarises changes in the set of players who were ranked in 2003 and 2004 and Table 4 summarises changes in the set of players who were ranked in 2004 and 2005. These tables categorise the players into 3 groups; those ranked in both of the 2 years of interest, those leaving the rankings in the second of the two years and those appearing in the rankings in the second year having not been ranked in the first year. There were no significant differences in the proportions of the 3 types of players between the female players born in H1 and H2 of the year from 2003 to 2004 ( 22 = 4.9, P = 0.085) or from 2004 to 2005 ( 22 = 5.7, P = 0.057). However, half year of birth did have a significant influence on the proportions of male players entering and exiting the rankings from 2003 to 2004 ( 22 = 12.3, P = 0.002) and from 2004 to 2005 ( 22 = 12.1, P = 0.002). Between 2003 and 2004 the ratio of new arriving male players to leavers was 3.8 : 1 for players born in H1 and 6.1 : 1 for players born in H2. Between 2004 and 2005 the ratio of arriving players to leavers was 1.3 : 1 for the male players born in the H1 and 2.2 : 1 for the male players born in H2. The greater number of H1 than H2 born male players who dropped out of the rankings in both 2004 and 2005 is the most noticeable pattern in Tables 3 and 4; the 291 H1 born male players dropping of the rankings in 2004 and 2005 is 73% higher than the 168 H2 born male players who dropped out of the rankings over the same period.

Table 3. Changes in the set of 1987 and 1988 born players who achieving ranking points in 2003 and 2004.

Table 4. Changes in the set of 1987 and 1988 born players who achieving ranking points in 2004 and 2005.

As well as analysing participation levels of 1987 and 1988 born players in the ITF junior circuit, it was desirable to monitor and compare their world rankings over the 3 year period. Table 5 summarises the end of year ITF junior rankings of the 290 female and 325 male players who had achieved ranking points in all 3 years. The female players’ rankings improved from 2003 before declining in 2005. The male players’ rankings improved considerably from 2003 to 2004, but there were different fortunes experienced by the H1 and H2 born players between 2004 and 2005. The H1 born players dropped 10 ranking points on average between 2004 and 2005 in comparison to the 79 places dropped by the H2 born players. A Mann Whitney U test did not find a significantly greater improvement in world ranking between the female players born in H1 and H2 from 2003 to 2004 (z = -0.327, P = 0.744) or from 2003 to 2005 (z = -0.938, P = 0.348) or between the male players born in H1 and H2 from 2003 to 2004 (z = -0.517, P = 0.129). However, the improvement in the median world ranking of the H1 born male players from 667th to 360.5th between 2003 and 2005 was significantly greater than the improvement from 701st to 432nd for the male players born in H2.

Table 5. World rankings of male and femal players born in the first and second halves of the year who had achieved ranking points in all three years (2003, 2004 and 2005).

Discussion

This study has tracked the participation of the 3071 players born in 1987 or 1988 who appeared in the ITF junior world rankings in 2003, 2004 or 2005. Despite only covering the first 3 years of a longitudinal study, some interesting patterns have already been observed. Firstly, while the number of 1987 and 1988 born male players achieving ranking points rose steadily from 2003 to 2005, the number of 1987 and 1988 born females decreased after 2004. An explanation of the fall in the number of 1987 and 1988 born female players in the ITF junior rankings in 2006 is that some had already commenced their senior careers. Indeed, there were 61 of these female players who were already ranked in the top 500 senior female players in the world at the end of 2005 (WTA rankings) compared with 11 of the 1987 or 1988 born male players who were ranked in the top 500 senior male players (ATP rankings). The earlier maturation in females than males (Malina, 1990) may explain the ability of larger numbers of female players to compete in the senior tour before the age of 18. There may also be a greater strength of depth in the men’s senior game than in the women’s senior game as it is more difficult for 17 and 18 year old male players to achieve top 500 rankings in the world senior rankings. Evidence of the greater strength in depth in the men’s game also comes from the 2006 French Open where 4 unseeded male players reached round 4 and 2 reached the quarter finals. There were no unseeded players in the same rounds of the women’s singles. O’Donoghue (2004) also found that there were fewer matches where players were defeated by lower ranked opponents in women’s singles than in men’s singles. The current results agree with previous investigations into tennis that there is a skewed season of birth distribution (Dudink, 1994; Baxter-Jones, 1995; Edgar and O’Donoghue, 2005) with more H1 born players participating in the ITF junior tour. However, the proportion of players born in H1 was not as high as the 85% reported by Baxter-Jones (1995) for elite junior players. This study has discovered that the proportion of players achieving ranking points who were born in 1987 or 1988 declined in both male and female groups to the extent that in 2005, the season of birth distribution was no longer significantly different to a theoretically expected distribution for the female players. The changes in the numbers of H1 and H2 born players between 2003 and 2005 shown in Table 2 result from the balance of players entering the rankings and players leaving the rankings as shown in Tables 3 and 4. The larger number of H1 born players who leave the rankings may be explained by some of these players not being as talented as their H2 born counterparts. Such player may have been able to achieve ranking points up to the ages of 15 and 16 as a result of their relative age advantage over H2 born players. This relative age advantage will decrease as the players mature. The relative age advantage enjoyed by the H1 players before the age of 16 may be largely physical, which would agree with the views expressed by Edwards (1994) that there are physical effects as well as psychological effects of relative age advantage. As these players become older, the physical advantage over H2 born players reduces which may lead to some H1 born players becoming discouraged when they are not able to compete as effectively as when they were younger. The psychological effects associated with such experiences may lead some to drop out of the sport. There are limitations in the methods used in the current investigation that must be recognised. Firstly, where players do not appear in the rankings, it may be due to injury or competing at senior level but being ranked outside the world’s top 500 senior players. Some players’ junior rankings decline because they have partially competed in the ITF junior tour but concentrated on senior tournaments. An example is Andrew Murray of Scotland who was the 9th ranked junior at the end of 2003 and the 8th ranked junior at the end of 2004. At the end of 2005, he was ranked 301st in the ITF junior rankings but 64th in the ATP senior rankings. This research will continue, following the careers of these 1987 and 1988 born players comparing the progress of those born in H1 and H2. There are many research questions that will be addressed by the longitudinal study. If the level of participation in senior Grand Slam tournaments changes in different ways for the players born in the different halves of the year, it will provide evidence of psychological factors associated with the relative age effect. It is possible that some H1 born players may not have as much genuine talent and will fall in the senior world rankings and drop out of the sport. The H2 born players may rise though the rankings feeling encouraged to prolong their careers. Alternatively, if the H1 players have been misidentified as talented, they may improve as a result of the opportunities of higher levels of coaching and competition (Rejewski et al., 1979). In conclusion, this research has applied a more dynamic approach to investigating season of birth effects in sport by following participation levels of a set of players over a period of 3 years. There was a skewed month of birth distribution in the 1987 and 1988 born players in 2003 to 2005, with a more pronounced skewed distribution in the male players. However, between 2003 and 2005 the proportion of players who had been born in H1 reduced in both male and female players.

Bibliografía

- Barnsley, R. H., Thompson, A. H. and Barnsley, P.E. 1985 “Hockey success and birthdate: the relative age effect” Canadian Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation, 51, 23-28.

- Baxter-Jones, A. D. G. 1995 “Growth and development of young athletes: should competition be age related?” Sports Medicine, 20, 59-64.

- Brewer, J., Balsom, P. D. and Davis, J.A. 1995 “Season of birth distribution amongst European soccer players” Sports, Exercise and Injury, 1, 154-157.

- Boucher, J.L. and Mutimer, B.T.P. 1994 “The relative age phenomenon in sport; replication and extension with ice-hockey players” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 65, 377-381.

- Dudink, A. 1994 “Birth date and sporting success” Nature, 368, 592.

- Edwards, S. 1994 “Born too late to win?” Nature, 370, 186.

- Edgar, S. and O’Donoghue, P.G. 2005 “Season of birth distribution of elite tennis players” Journal of Sports Sciences, 23, 1013-1020.

- Malina, R. M. 1990 “Growth, exercise, fitness and later outcomes” In Bouchard, C. and Malina, R.M. (Eds.) Exercise, fitness and health: a consensus of current knowledge, Champaign, Il: Human Kinetics, 637-653.

- Musch, J. and Hay, R. 1999 “The relative age effect in soccer: cross-cultural evidence for a systematic discrimination against children born late in the competition year” Sociology of Sport Journal, 16, 54-64.

- O’Donoghue, P.G. 2004 “The advantage of playing less sets than the opponent in the previous two rounds of Grand Slam tennis tournaments” In Lees, A.,

- Khan, J.F. and Maynard, I.W. Eds.) Science and Racket Sports III, London: Routledge, 175-178.

- Rejewski, W., Darracott, C. and Hutstar, S. 1979 “Pygmalion in youth sport: a field study” Journal of Sport Psychology, 1, 311-319.

- Simmons, C. and Paull, G.C. 2001 “Season-of-birth bias in association football” Journal of Sports Sciences, 19, 677-686.

- Thompson, A., Barnsley, R. and Stebelsky, G. 1991 “Born to play ball: the relative age effect and major league baseball” Sociology of Sport Journal, 8, 146-151.

[congreso:_deportes_raqueta]